You know, when it comes to lusting for naked skin, art history is actually surprisingly even-handed. You can get your eye candy fix whichever way you’re wired.

Take a look at Reginald Arthur’s 1892 oil painting ‘The Death of Cleopatra’, for example:

(Source: Wikimedia Commons; image is in the public domain.)

Now, you might look at this painting and go, “Uhm…why is Cleopatra dying in a see-through dress, exactly? And why are her breasts exposed? Why that whole erotic pose in general? And…hang on, do dying people actually boast a facial expression bordering on rapturous ecstasy? La petite mort, indeed. Also…was that snake added because of the myth about how she died or, you know, because of its obvious phallic implications?”

In short, you might wonder why this supposed depiction of death and agony…looks like some exotic, Sarah-Bernhardt-inspired, fin de siècle sex dream. Why did Arthur paint her like this?

Well, if he lived today, instead of a century ago, and used internet-meme speak, then I’m guessing he would give you a wink and reply, “For science, love. For science.”

Artists have, at all times and in every corner of the earth, come up with flimsy excuses for painting naked skin, and those who lived in late 19th-century England, say, with its strict Victorian mores, were well advised to pick a historical or mythological or religious theme in order to have plausible deniability on the nudity front. And they gave museum audiences back then a brilliant excuse, too, of course. (“I’m salivating over this painting for its religious subject matter, don’t you know?”) The artist and the viewer were (and still are) complicit in creating pretexts for their shared gaze.

What, you don’t believe me when it comes to the ‘religious’ part, dear reader?

What do you think all those paintings of Saint Sebastian are all about? Religion?

Don’t make me laugh.

They were painted, so the artists in question had an acceptable justification to air their predilections in public without ruffling any feathers. After all, you can’t keep painting just Adam and Eve all day long; you wanna switch things up a bit from time to time, to keep it fresh, so to speak.

Plus, paintings of Saint Sebastian are a prime example of how even-handed art history is in this respect: Male nudes (not just female ones) were always represented in this field, always a natural and integral part of human expression through art.

Look at this 18th-century stunner, for example:

(Source: Wikimedia Commons; image is in the public domain.)

I mean, come on, François-Guillaume Ménageot (1744-1816) didn’t even bother with the customary arrows piercing Sebastian’s skin in this one. Like…the whole thing barely pretends to be pious anymore.

“Ooh, yes, let’s quickly add that thin piece of rope to his wrist, so it’s all above board, okay?...Blood? What is blood?...Ugh, blood is icky. Why don’t we just stick to meticulously shaded musculature instead. What, you don’t think that facial expression makes him look like a martyr who’s being brutally tortured for his faith? Well, that’s your dirty mind, dear viewer. That’s on you.”

Yeah, and I’m sure Sebastian’s hair just happened to spill over his shoulder in that perfect wave when he was pierced by those (invisible?) arrows outside the city gates, uhm, yeah…

Paintings like this are almost winking at us, aren’t they? They turn us, the museum audience, into accomplices to the artist’s deed:

He pretends there’s a deeply spiritual dimension to the painting by adding some measly piece of rope to it, and like the prissy royal academicians that we are, we nod along and mutter with a straight face, “Yeah, yeah…totally religious painting, that.”

The symbiosis between the artist and us, the audience, is centred around our shared thirsty eye here.

And the painting itself isn’t going to tell on the artist, is it? (“Oi, is that a brush in your pocket or are you just happy to see me?”)

Should we mention that size does actually matter in art? We’re dealing with an almost life-size painting of Saint Sebastian here.

Yeah, take that, 21st-century philistines secretly staring at dirty pictures on your tiny smartphone displays in the dark! This painter just took his desire and unashamedly turned it into a giant canvas, then had it framed and proudly exhibited it at the Salon for everyone to feast their eyes on.

What, you still think this is a religious painting, dear reader?

Do I have to bring out the big guns for this one?

Okay, you asked for it. Here it comes:

The whole field of Saint Sebastian depictions boasts an inexhaustible wellspring of erotic art, of course. There are, in fact, so many examples that I could go down rabbit holes for months on end here, but just for you, dear reader, I’m going to reveal my absolute, one-and-only, personal all-time favourite Saint Sebastian painting. Deal?

As you can see, this one is quite a bit older than the other one. It’s called ‘San Sebastiano trafitto dalle frecce’ (Saint Sebastian pierced by arrows), and nobody knows who painted it. It was at times attributed to Nicolas Régnier or his circle. But the only thing that’s really certain is that it was painted in the Caravaggesque style by a very experienced and mature artist sometime around 1620-1630.

We should be fair to the anonymous master here: At least they added a few arrows for plausible deniability. The artist really tried, okay? Come on, let’s give them a big hand, everyone. And a C+ for effort.

But we won’t be fooled: It’s still so obvious what happened here. Even the arrows seem like they’re just a sly allusion to penetration at this point. Because, boy, that pose…the way the young man is pretty much, uhm, all laid out for the viewer like a tasty treat on a silver platter…Good Lord.

From the unusual pose (Sebastian is usually depicted upright and tied to a tree instead of sprawled out like this) to the equally unusual perspective (half-turned and mapped out from the crown of his head down to his knee), this painting just breathes quiet eroticism.

And just in case you’re wondering: That’s an almost life-size painting, too. It’s even larger than the other one – by which I mean it’s longer in width, accentuating the way in which Sebastian is splayed out there like that.

Did you notice the artist’s treatment of his skin? Sebastian’s youthful cheeks are flushed ever so slightly. (I wonder why? Has it got something to do with the fact that his thighs are parted like that?) And if you absolutely want to believe that this is a religious painting, you can, of course, pretend that he has his hand outstretched towards the light of the Lord and whatnot. But doesn’t it look at least a little as if he were beckoning his lover back to him? I mean, his rib cage, that entire chest looks like it’s still heaving…

Note, once again, what the unknown artist turns us, the viewers, into here: Do you really think we, the audience, are Jesus? Seriously? I mean, if you’ve got delusions of this sort, be my guest. But let’s be honest here for a second: The painter turns us into this man’s lover. We are being called back to his side with that gesture, asked to come back and ravish him again. We are the other person in this painting’s fictional universe. We are the ones devouring him with our gaze. We are the ones that hand is reaching for. Make no mistake, 17th-century people weren’t dumb; they knew what they were looking at in a painting such as this.

I mean, just look at the way Sebastian’s bottom lip is glistening in the light or the way his erect nipples are accentuated here; one of them catches the light ever so slightly, too…Yeah, do you wonder right now whether a ticket to the Museo Garda Ivrea comes with access to a cold shower on the premises?

Perhaps you feel like objecting now, “But, tvmicroscope, surely this favourite Saint Sebastian painting of yours is an exception. Surely, men aren’t usually shown in this utterly passive state with the viewer holding all the power over them. Surely, they aren’t usually displayed in all their vulnerability. Surely artists only paint female subjects in this way, right?...I mean, think of all those sleeping nymphs and such. Art is usually created, so the artist and the viewer can jointly gawk at defenceless, half-naked women – not men, right?”

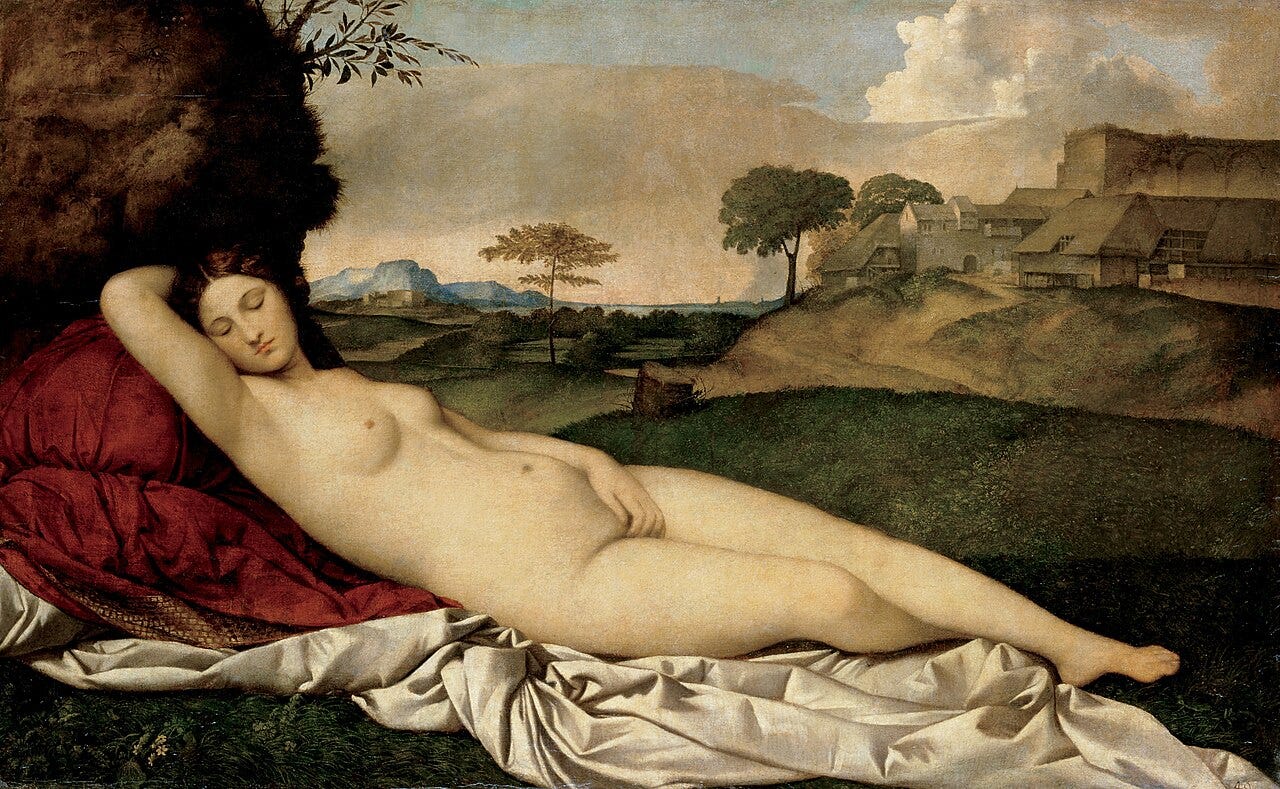

I know what you’re thinking of, dear reader: You’re thinking of paintings such as Giorgione’s 1510 ‘Sleeping Venus’, am I right?

(Source: Wikimedia Commons; image is in the public domain.)

And sure, they exist. There are many paintings like this.

But you’re still wrong.

You’re thinking with your cinema brain, not your art history brain. And while, yes, films and TV shows have sadly been pretty one-sided in this respect for over a century now, the other visual arts are a different matter altogether. The moment you delve into art history, you will realize that art had so, so many centuries to develop, grow and flourish that there really is an avenue for everyone to explore, whatever their preferences may be.

So, yes, you get your sleeping vulnerable men being gazed at by women, as well. Consider John William Waterhouse’s 1899 ‘The Awakening of Adonis’, for example.

(Source: Wikimedia Commons; image is in the public domain.)

Note how Waterhouse basically turns us, the viewers, into cherubs here. We’re all part of this particular audience. (Why did you think the circle of cherubs is broken at the exact spot where we, the museum audience, is probably standing in front of the painting? It’s because we are a part of that circle!) We’re all like those chubby-cheeked fellows in the painting itself. Their gaze is our gaze. We’re all part of this spectacle, and we’ve all become complicit in it: We’re all watching Venus as she rouses the most beautiful mortal man on earth from his slumber. And in case you don’t have your Ovid at your fingertips: Venus is the one actively pursuing him, not the other way around. And that’s the way the painting stages the scene, too: He is all vulnerable passivity and sleepiness here. The ‘awakening’ carries obvious sexual connotations, of course: She is initiating him into the ways of desire, love and passion.

Giorgione gives us Venus asleep, passively displayed for the viewer’s gaze, who can fantasize about ravishing her. Waterhouse gives us the opposite: Venus wide awake and initiating that sexual relationship with Adonis. It’s the man who’s asleep here and who needs to be touched and ‘awakened’.

By the way, the red anemone flowers right next to Adonis’ arm in the painting foreshadow his death: He is a mortal. She is an immortal goddess. (There’s a power imbalance for you!) He will be gored by a wild boar while out on a hunt, and then he will die in her arms as she weeps. Her tears will mingle with his blood and turn into those flowers.

Anyway, in films, you don’t really get men all laid out for a woman’s eye to appreciate all that often. Art history can do that for you!

If you’re a lady, then…you’re welcome, dear reader. And if you’re a chap, admit it, you liked the painting, too. (And if you’re a straight man…like…really? Are you sure?)

What are you saying there, dear reader?...Oh, that one’s not naked enough for you? Come on, you’re really looking for fault with a magnifying glass now!

So, you’re saying my argument about art history being more even-handed only holds water if I show you an example of a male subject getting his kit off?

Again, you’re thinking with your cinema brain. And while yes, cinema and television are pretty one-sided in this respect, you can’t really say this about art history – at least not to the same degree. Painters really had so, so many centuries to turn their gaze whichever way.

As for men sleeping, passively displayed for and exposed to the viewer’s gaze, you can’t go any better than depictions of the Endymion myth (pretty much all of them; and there are a lot of them out there). Here, have Nicolas-Guy Brenet’s 1756 ‘Sleeping Endymion’ to round out the eye candy for today:

(Source: Wikimedia Commons; image is in the public domain.)

And just in case you’re wondering, the whole point of that myth is that he’s sprawled out like this in front of a woman: The myth tells us about the goddess Selene, the allegorical personification of the moon, who is burning with mad passion for the beautiful mortal Endymion. He is variously described as a shepherd, a hunter or an astronomer – one of the professions, in any case, that require you to be out and about when the moon is high. That’s when she spots him, gazes at him…and instantly desires him. And then she has him put into eternal slumber to entrap him forever and have her way with him till the end of time…

You do, of course, understand that I’m being slightly tongue-in-cheek in this introduction, right? Obviously, I’m not really trying to denigrate or ridicule some of the greatest works of art in the Western tradition.

And you have probably also picked up on the fact that I haven’t chosen these paintings at random, that I have, in fact, picked them very carefully. They tell us something about what an artist can do to us, the viewers. Art doesn’t exist in a vacuum; it only turns into art once it establishes a relationship with the viewer. Without gazing, there is no art.

Artists do more than just explore the relationship between the subjects in their paintings; they establish a relationship between the canvas and us, the viewers standing in front of it. And yes, at times they can turn us into voyeurs. Willing voyeurs or reluctant ones. Viewers who question what is happening to them and what they’re being turned into…or viewers who go through this transformation unwittingly.

(All of this will be very important once we get to the film part of this post under the fold, and I want you to keep this in mind.)

There’s obviously so much more we could say about these paintings: Think of the exotification and orientalism angle of the ‘Death of Cleopatra’, for example. Or think of the topic of iconographic justification of nudity in art…But most importantly: If the only way people can approach a painting anymore is with the lens of political activism in mind, if the only thing they can say about art is ‘-ism’ or ‘-phobia’, then they most likely don’t understand what art is and what it is for. Criticism is all nice and well, but at some point you have to actually start to analyze the art, too: to look at the symbolism encapsulated in it, to examine its brushstrokes and colours, in short to look at how masterfully it employs the techniques that it uses…and perhaps discover the universality of it along the way, something that goes beyond whatever is politically fashionable in the here and now, something that transcends time and space, something that gives you back your childlike ability to look at things in awe and wonder and marvel at what the human hand is capable of creating. So, yes, there is so, so much more we could say about these paintings…

One of the things you might have noticed about them is that they were all painted by men, and yet I said that there was and always is a triangular relationship between the artist, their creation and the viewer, which obviously implies that the artist’s identity at least merits a closer look, as well.

Art history knows of many great women painters (and that topic in and of itself would warrant a whole separate post and not just because of the great obstacles they often faced, but because of their art itself, of course), but let me just give you one example because it fits our discussion. (And yes, this painting will be the example where the whole topic of the gaze takes a turn for the dark.)

You see, artists were often keenly aware of the fact that gazing at naked skin isn’t just a harmless pastime, that there’s a danger inherent in it and that this danger cuts both ways.

This is, of course, the great Artemisia Genteleschi’s famous 1610 painting ‘Susanna and the Elders’ (one of several depictions of the same subject matter by the artist, as a matter of fact):

(Source: Wikimedia Commons; image is in the public domain.)

She painted it at the tender age of 17. And it depicts the famous passage from the Old Testament that recounts the story of Susanna: Two men spy on her while she’s bathing and decide to rape her. (Their gaze is a weapon here, we are to understand.) They falsely accuse her of adultery in order to pressure her into having sex with them. She refuses. The Biblical story has a happy end: The two men are exposed; their lies are debunked, and they are put to death.

Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the artist’s real life story: Genteleschi was raped by two men (one of whom was her painting instructor). And if you don’t want to give yourself nightmares for the rest of the week, I suggest you stay away from google and refrain from researching what so-called ‘civilized’ society did to her afterwards and how it treated the rapists.

While the painting itself was painted in the year prior to the rape, there are at least some scholars who believe that she might have been harassed and pressured by the rapists long before the rape occurred. It’s at least possible that that’s what she was trying to express in that painting: We don’t just get a defensive hand gesture in it; Susanna’s facial expression spells clear distress at being watched.

The Biblical story itself has fascinated painters for centuries, of course, precisely because of that danger inherent in the gaze: The visual arts are all about the eye, after all. Without us, without the viewers, there wouldn’t be any paintings. Art thus becomes a tightrope walk between showing, exposing and hiding. What type of gaze is necessary in order to establish a relationship between the viewer and the canvas? What type of gaze is twisted and immoral? Is there even a clear boundary between the two?

Genteleschi poses that exact question in her painting: While Susanna is defensively raising her hands, trying to ward off the two voyeurs in the painting, her naked body is actually turned towards us!

Are we actually any better than those two men whispering to each other, conspiring to commit that crime? Have we perhaps only come to the museum in order to look at her naked form? Are we voyeurs, too? Whispering and staring at her bare skin…

Genteleschi cleverly makes us part of the painting. Our roaming eyes, our gaze, our desire is called out loudly here.

Susanna is in imminent danger because of that gaze. Our eyes are a threat to her.

But when you think about it…they’re a threat to our own lives, as well: Unlike Genteleschi’s real-life rapists, the two men in the Biblical story were sentenced to death. Our voyeurism in front of the canvas should be punished, we are told here, that’s how heinous a crime it actually is.

Think about that the next time you visit a museum…

Which, in turn, means that, as an artist, you sometimes have to depict that naked skin in order to make a point. That painting simply wouldn’t work if Susanna were fully clothed. If the artist had treated Susanna with the respect she deserved, we, the museum audience, wouldn’t be able to gawk at her in the same way those two criminals in the painting do…which would defeat the whole purpose and undermine the message of the painting, right?

The triangular relationship between the artist, the subject and the viewer means that the artist will sometimes force us to step into the painting, to put ourselves in the shoes of one or even several of the subjects depicted on that canvas. And sometimes this will make us feel uncomfortable, but it will be necessary, nonetheless, if the artist in question wants to convey the message they have in mind.

Which brings me to the topic of today’s post…

All the examples given above have one thing in common: They were all painted. They might deeply move us, but they’re not moving pictures in and of themselves.

So, what do actual movies, you know…motion pictures, do? How do they depict sexual desire? And what techniques do they use for that? What does the camera do exactly to achieve what sort of effect?

And how dangerous do filmmakers deem the eye of the camera vs. the eyes of the audience vs. the eyes of the characters in a scene like that?

If you’re following this little blog, you’re most likely here because of ‘Young Royals’. Today we will talk about something that ‘Young Royals’ never does. (And that’s not an oversight by the creators of that show, that was clearly a deliberate choice.)

So, what exactly is it that ‘Young Royals’ doesn’t do and that a million other shows and movies do? Which techniques does ‘Young Royals’ eschew and why? And how does that serve the message of this show?

We will have to talk about different types of shots and the technicalities of camera movement quite a bit for this, but if we do it right, this will (hopefully) also have a useful side effect: You’ll end up with a little list of films to watch (or perhaps re-watch?). It could, of course, also turn into a list of films to avoid. Let’s see how it goes.

Oh, and we absolutely have to talk about that ‘first kiss’ scene between Wilhelm and Simon because there’s something in it we haven’t discussed before; we have to talk about a filming technique employed in that ‘first kiss’ scene.

And yes, yes, of course, we will talk about that one legendary sexual-desire scene: The infamous ‘bathtub scene’ between Matt Damon and Jude Law from ‘The Talented Mr. Ripley’!

That one we will positively take apart to understand what is going on there and what exactly the filmmakers are doing cinematically. (So, you know…in case you need to take your heart medication before diving headfirst into a scene like that, do it now! Go get your fan ready, too, in case you get all hot and bothered. Maybe do a few breathing exercises, just in case…)

So, come along, and we’ll take a deeper look at that murky bathwater (and naked Jude Law, who am I kidding…).